BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space: Interview With Changingday CEO Alison Lang

Virtual Reality gaming has the opportunity to really change the shape of gaming experiences. Players have already witnessed how VR headsets can make horror games even more intense, using the additional immersion of the media to truly bring the scares. However, there’s even more that can be done, and this is something that BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space from developer Changingday is aiming for.

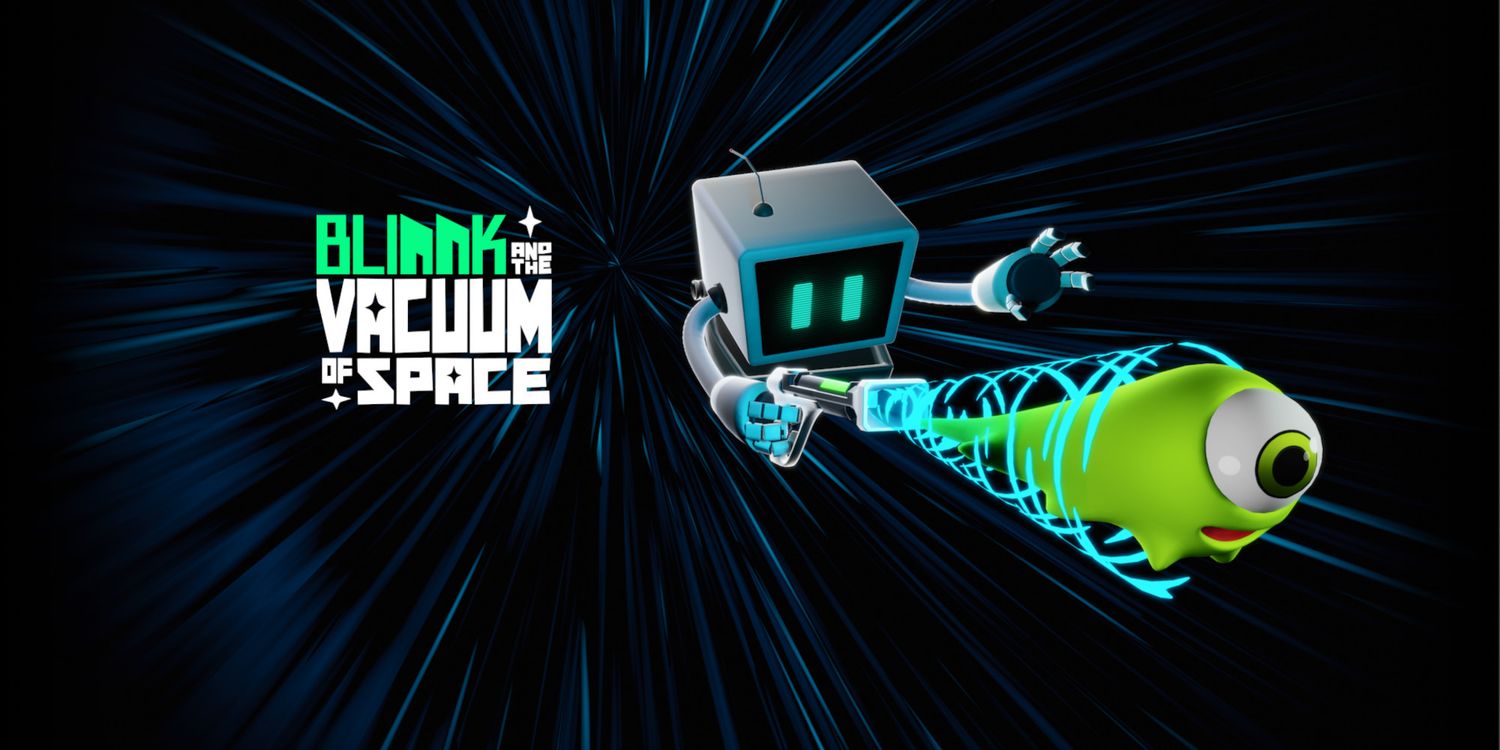

BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space is a space-based adventure VR game with gameplay designed specifically for autistic players. The player is a new employee of Norp Corp, and must try and track down a mischievous bunch of creatures called the Groobs before they run rampant across Norpopolis space station. BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space provides a selection of everyday scenarios, free of fail states, to support and challenge its players.

Screen Rant spoke with Changingday CEO Alison Lang about BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space, the benefits of VR for autistic players, and the game’s development process.

Why did you want to create BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space? Why do you feel it’s an important video game to be developed?

Alison Lang: As parents of an autistic person, we have spent many years doing what we can to help and support our daughter, so we’ve long been aware that effective resources are few and far between. When we learned about the powerful and lasting effect that VR can have on autistic people, it was clear that there was an opportunity do something for autistic people that they would really enjoy and that could help them cope with everyday life.

VR is already being used as a therapeutic tool, but it seemed to us that we could take a different path. Autistic people are individuals who are proud of their autism. It’s a characteristic to be supported, not a flaw to be fixed. They love playing video games – research says 41.4% of autistic adolescents play video games against 18% of neurotypical peers – but existing games, understandably, can present difficulties because they are not designed with the autistic player in mind. There may be challenges they just cannot do, which means they can’t complete the game. Character motivations within the game may be impossible to understand. They often cause sensory overload through too much sound, or colour, or shock, which an autistic player just cannot cope with.

We decided to develop a VR game designed specifically for autistic players that took account of what excites them, whilst addressing the design issues that may compromise their enjoyment of other titles. A game that autistic people would want to play because it was fun, but which incorporated real life scenarios designed to help the player cope with everyday life.

What benefits do you feel that video games have as a medium for supporting autistic people with everyday experiences, over other formats? And how do you feel that VR is even more beneficial than a more traditional video game?

Alison Lang: Our research showed that one of the key attractions for an autistic player is the ability to escape from a world which they don’t always understand, and which makes no real effort to understand them. A world where they are constantly being pushed to behave in a way that doesn’t come naturally to them.

The immersive nature of VR transports the player more completely than traditional video games. It puts them in a world they believe in, where they are in control and which lets them go at their own pace. In a VR world, they can be who they are and play on their own terms, without worrying or stressing about what’s going on around them.

Perhaps most important of all, the resulting boost in confidence and ability to cope has been shown to last into the real world once the game is over.

How have autistic people been involved in the development of BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space? What steps have you taken to ensure that autistic people are at the heart of its creation?

Alison Lang: We knew from the outset that this was not going to be an easy undertaking. Autism is barely understood, and the variety and potential amongst autistic people is vast.

We had our own experience of autism through our daughter and her friends, but we knew we had to build on our understanding through research.

As well as looking at the latest academic papers on autism, gaming and VR, we conducted a detailed online survey of 177 autistic gamers to learn more about their likes, dislikes and challenges. We also developed a series of prototypes to explore issues like delivering instructions and prompts, preferred styles of game and in-game characters, methods of accessibility, and gameplay and level design. The reactions of autistic players were tested against a neurotypical control group in 80 sessions.

This research has informed every decision we’ve made to try to make the game as enjoyable and beneficial as possible. It was also an ideal way to ensure our team understood our audience and the challenge of what we were trying to do.

In addition, we set out with the aim of involving as many autistic people in the process of building the game as possible. We have a full-time autistic member of staff who has played a central role in the design of the game. We worked with two autistic interns in the development of our accessibility options. We are constantly testing our work and our assumptions with autistic people, and will be undertaking another testing session of the full game before release.

Perhaps the biggest challenge, however, is accepting that we won’t get everything right. After release we will be gathering as much feedback from players as possible so that we can incorporate their suggestions into future games.

How have you approached sensory sensitivity with BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space? Given how unique autistic people’s experiences are, what flexibility and customization options do players have for their VR experience? What other accessibility options are embedded in the game?

Alison Lang: Autistic people are not easily pigeon-holed. They are as varied and unique as any group of people. There are characteristics and behaviours which many of them will share, but a one-size-fits-all approach is impossible to achieve. This is particularly true with hypersensitivity issues.

Our research allowed us to develop a series of design protocols so that we could avoid the most common issues autistic players have with colour, sound, design and gameplay, so every aspect of the game is planned to minimise the risk of sensory overload. However, some players will have particular issues, so we have implemented a comprehensive accessibility menu to allow the player to adjust a wide range of sensory inputs. For example, they can turn down, or even switch off sounds that they find particularly intrusive, individualising the experience according to their own sensitivities.

This accessibility menu is reached at the push of a virtual button from anywhere in the game and sits in calm space that acts as an escape from the excitement of the game itself. In addition, there is a sensory area in the game where the player can relax and enjoy several calming features.

How have you made sure that BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space provides support to autistic people without it being masking or camouflaging autism?

Alison Lang: VR is the key here. Research suggests that when autistic people are immersed in a virtual world, any deficit they experience in the real world all but disappears. In the VR world, the need to mask and to fit in with the expectations of others is no longer present, and they are quickly able to relax and be themselves. The game allows them to be autistic and supports the choices they make within the virtual world.

The levels and tasks within the game are designed with this in mind. There are scenarios which echo real world situations that we know many autistic people find difficult – dentists, airport security or even the park, for example. In the game, they can approach these with new confidence, knowing that they can act as they wish without upsetting the world around them.

And because the activities are fun, the situations are de-mystified and made normal. Other levels are designed to support strengths like fixing things, working with patterns and music, to bolster the confidence of the player.

The UK games industry is reportedly more neurodiverse than the UK average workplace. Do you think there’s an opportunity to share more stories about neurodiversity in the medium? Do you think that the games industry can become an even stronger source of employment for autistic people, and how would you like to see that change happen?

Alison Lang: All the research we have undertaken suggests that gaming, and VR in particular, is an invaluable resource in supporting and improving the lives of autistic and other neurodiverse people. The escape, the control, the confidence that being able to face a world on your own terms gives is hugely beneficial. This is more than an opportunity to share stories, it’s a necessity to give neurotypical people an outlet that they have not been able to access up until now.

Part of this will be bringing more neurodiverse people into the industry. The strengths that many autistic people have fit well with the industry – the ability to work with patterns, see trends, to take different creative decisions, all present real potential, not just for the development of games for autistic and neurodiverse people, but for the future of the industry itself. There is already considerable neurodiversity in the industry, but it can only benefit by increasing that level of integration.