Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid: 8 Things That Still Hold Up Today

The western genre has been a staple of Hollywood filmmaking since the very beginning. Its tropes are so well-worn and outdated that they got deconstructed by satirists like Mel Brooks and revisionists like Sam Peckinpah half a century ago. As a result, a lot of the genre’s traditional classics don’t hold up today.

The westerns that have stood the test of time are the ones that subverted the audience’s expectations. A prime example is George Roy Hill’s 1969 anti-western masterpiece Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a buddy comedy about two real-life outlaws fleeing from justice. With its engaging lead performances and breathtaking cinematography, this classic film continues to be a favorite for cinephiles and casual viewers alike.

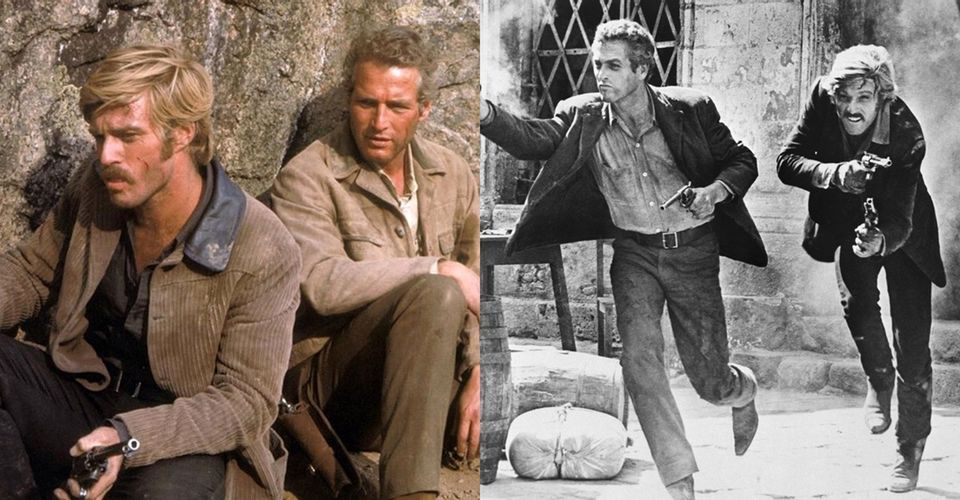

8 Paul Newman And Robert Redford’s Buddy Dynamic

The heart and soul of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is the friendship between the title characters. They’re infamous bank robbers, but the audience can relate to them because they care about each other and watch out for each other.

This buddy dynamic was brought to life beautifully by the perfectly matched leads Paul Newman and, in one of his best roles, Robert Redford. The two generate a genial chemistry that engages and charms the viewers even when the duo commits numerous bank robberies and act like cads. The actors’ on-screen bond proved to be so tangible that they reteamed four years later for The Sting, which garnered an Oscar nomination for Reford and won Best Picture.

7 The Anti-Western Story

William Goldman had a tough time shopping his Butch Cassidy script around Hollywood because its true-to-life story went against the grain of so many western tropes. When the heroes are in trouble, they don’t face it head-on like John Wayne or Gary Cooper; instead, they flee across the border. And the term “heroes” is applied loosely because Butch and Sundance are notorious outlaws.

But these subversions of the expectations of the western genre – particularly in 1969 when the genre’s popularity had peaked and the whitewashed myths were being broken down – ended up being the main selling point of the movie. With its morally ambiguous heroes and downbeat ending, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is the perfect example of an anti-western. Unlike the other major western of 1969, the John Wayne picture True Grit, Butch Cassidy didn’t lionize its titular heroes who indulge in mythmaking that so many American westerns had done in the past. Instead, it focused on the brutal realities of a life of crime and exposed the corruption of the officials that are out to get the pair.

6 Burt Bacharach’s Contemporary ‘60s Score

Burt Bacharach was such a staple of ‘60s culture that he was tapped for a cameo appearance in every single Austin Powers movie. His Oscar-winning musical score for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is part of what makes the movie such a quintessential snapshot of late-‘60s Hollywood cinema.

Instead of using operatic orchestrations to mimic the western music of composers like Morricone and Bacalov, Bacharach went for a more contemporary style that paired with the movie’s use of modern social attitudes. In the now-classic song from the movie “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head,” Bacharach created a song that was simultaneously romantic and a bit of a downer. The song suggested that while the trials of life may weigh Butch down, it doesn’t stop him from living or romancing Etta Place.

5 The Offbeat Humor

A lot of the most highly acclaimed revisionist westerns are grim, grisly affairs. The Wild Bunch, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Great Silence, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly are all brilliant but bleak movies that focus on the violence and bloodshed of the American West to destroy any romantic notions the audience may have about that particular time and place in history.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid deconstructs the same genre tropes and offer the same subversive antiheroes, but with an offbeat sense of humor. William Goldman’s script is filled with well-placed comedic moments that Newman and Redford deliver spectacularly. Right before the duo engages in a firefight, Butch confesses that he’s never shot anybody and, with hysterical comic timing, Sundance quips, “Hell of a time to tell me, Butch…” It’s moments like these that helped Goldman win the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay that year.

4 Katharine Ross’ Engaging Turn As Etta Place

Paul Newman and Robert Redford star in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid as the title characters, but the movie has a third, equally acclaimed lead in Katharine Ross. Ross gives an engaging performance as Etta Place, Sundance’s lover who joins the pair when they flee to South America.

While Butch and Sundance’s banter is the central conflict in the movie, Etta provides a great foil for both characters. She provides the movie with a moral center that prevents the pair, especially Butch, from indulging in their self-destructive tendencies. Once she returns to America, however, Etta’s absent sensibility and decency cause the heroes to make poor decisions that eventually lead to their demise at the end of the film.

3 William Goldman’s Sharp Dialogue

Well-written dialogue ages like a fine wine. The dialogue in old westerns tends to be stiff and inaccessible, with clichés like “I don’t want any trouble” and “head them off at the pass.” The outdated way that characters talk in some of the best westerns from the ‘50s and ‘60s can be alienating to modern audiences.

But the sharp dialogue in William Goldman’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid script – particularly the bickering between Butch and Sundance themselves – could’ve been written today. The duo’s snappy conversation about whether to jump off of a cliff into a river is a prime example. Part of the reason why the film’s dialogue has aged well is that Hollywood has imitated it since the film’s release. Films such as Lethal Weapon and virtually every buddy cop movie has tried, and mostly failed, to mimic the casual back-and-forth verbal exchanges that made Butch Cassidy so engaging.

2 The Bittersweet Ending

The final scene of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is one of the most iconic ambiguous endings in film history. Surrounded by local police and the Bolivian Army, Butch and Sundance remain optimistic in the face of certain doom, sure that they can escape to Australia. When they run out with guns cocked and ready to fire, Hill freezes the frame over the sounds of the Bolivian troops opening fire, sealing the duo’s tragic fate.

The bright-eyed optimism of Butch and Sundance’s last stand in the face of insurmountable odds makes this ruthless, painful, inevitable ending surprisingly inspiring. This may be their final moment, but the duo will go out the way they lived their adult lives: standing tall with guns blazing.

1 Conrad Hall’s Breathtaking Landscape Photography

Conrad Hall, the cinematographer behind such classics as Cool Hand Luke and In Cold Blood, not to mention fellow western The Professionals, won a much-deserved Academy Award for his eye-popping work on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Director George Roy Hill went to great lengths to get his cast and crew out to real locations so he could shoot freely. In sequences like the super-posse chasing Butch and Sundance through the mountains, Hall captures breathtaking wide shots of landscapes in the unforgiving wilderness. These shots were not only gorgeous to look at but were key in framing the titular duo, whose grandiosity and slightly inflated egos were diminished by the sheer size and spectacle of the locations they were traveling in.

About The Author