The Odd-Numbered Star Trek Movie Curse Explained (& Is It True?)

What is the odd-numbered Star Trek movie curse, and does it hold any weight? Veteran fans of the Star Trek world will be all too familiar with the famous odd-numbered movie rule, but as the franchise continues to extend its reach and appeal to newer, younger audiences, this unique and fascinating piece of Star Trek mythology becomes relevant once again. In the decade following the cancellation of the original Star Trek series, the adventures of Kirk and Spock had performed very well in syndication and the series’ already passionate fan base had surged in the Enterprise’s absence.

This burgeoning popularity led to the release of Star Trek: The Motion Picture in 1979, which in turn triggered a whole new rebirth for the franchise on the silver screen, spawning a string of movies that would reach double digits and encompass three separate casts. While it’s impossible to deny that the Star Trek movie series was successful as a whole, reaction from fans and critics varied wildly with each release and, after a while, a pattern started to emerge that the Trek faithful couldn’t help but notice.

Over time, the Star Trek movie rule has passed into Hollywood legend, becoming trickier to keep track of following the J. J. Abrams 2009 reboot. The curse is still spoken of today in certain geeky circles, but was it ever accurate and, if so, does it still ring true in 2019?

What Is The Odd-Numbered Star Trek Movie Rule And Where Did It Come From?

Star Trek held a constant cinematic presence in the 1980s and 1990s, and soon became Paramount’s most important big screen property. As the franchise began to develop, however, fans in the mid-1980s began to point out an emerging pattern regarding the big screen adventures of the Enterprise: only the even-numbered films were any good.

This phenomenon seems to originate as early as the third movie, but came to widespread prominence following Star Trek V: The Final Frontier‘s poor reception. By 1991, the odd-numbered Star Trek theory had gained such traction that famous film critic, Roger Ebert, was making open references to it during his discussion of Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country with Gene Siskel. By the Next Generation era, the curse had been generally accepted as fact, and Jonathan Frakes even joked about the pattern prior to directing the odd-numbered Star Trek: Insurrection which, incidentally, very few people liked.

The odd-numbered Star Trek movie rule has now become an integral part of geek lore, and has even been referenced in the wider realm of pop culture. For example, Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright’s quirky sitcom, Spaced, sees Pegg’s character muse, “Sure as day follows night, sure as eggs is eggs, sure as every odd-numbered Star Trek movie is sh*t.” References such as this helped cement the Trek movie curse into the cultural consciousness, and the irony didn’t escape Pegg when the actor’s later career found him writing the script to Star Trek: Beyond – the thirteenth entry in the series.

Is The Star Trek Movie Curse Accurate?

Considering the fan base had been eagerly awaiting new material for a decade, Star Trek: The Motion Picture received a decidedly mixed response. Lacking the pacey intergalactic action that formed a central part of Trek‘s TV popularity and bloated with expensive effects, audiences were not blown away by the Enterprise’s first cinematic outing. With a greatly reduced budget, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan returned to the core principles and themes of the TV series, but added a modern Hollywood sheen, resulting in a film that many fans still claim to be the pinnacle of Star Trek‘s movie output.

Having struck upon a successful formula, Star Trek III: The Search For Spock followed on directly from its predecessor, but the general consensus upon release suggested the threequel failed to hit the heights of the previous film, largely thanks to a weaker plot and an aging cast. Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home took a vastly different approach, warping the crew of the Enterprise into the past for a more light-hearted caper, and audiences generally appreciated the shift in emphasis. After sitting back while Leonard Nimoy directed two movies, William Shatner could take no more and demanded the director’s chair for Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, the biggest critical flop since the original movie. Fortunately, business picked up again for the Klingon-centric Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country.

The seventh film, Star Trek Generations, was designed as a torch-passing from the original Enterprise cast to the Next Generation era and should’ve been suitably epic. Instead, most fans and critics felt the 1994 film was a mediocre effort, but Picard and co.’s crowning cinematic moment came in 1996’s Star Trek: First Contact. The ninth movie, Star Trek: Insurrection, once again suffered a dip in quality.

Up until this point, the odd-numbered Star Trek movie rule works perfectly. Although not every odd release is as bad as Simon Pegg would have you believe, there are certainly instances where a strong, even-numbered release is followed by a more average effort that curtails the franchise’s momentum. The first real anomaly is Star Trek: Nemesis, the “final” mission for the crew of Enterprise-D, which received the same muted response afforded to Star Trek: Insurrection four years previously, finally breaking the odd-numbered movie rule.

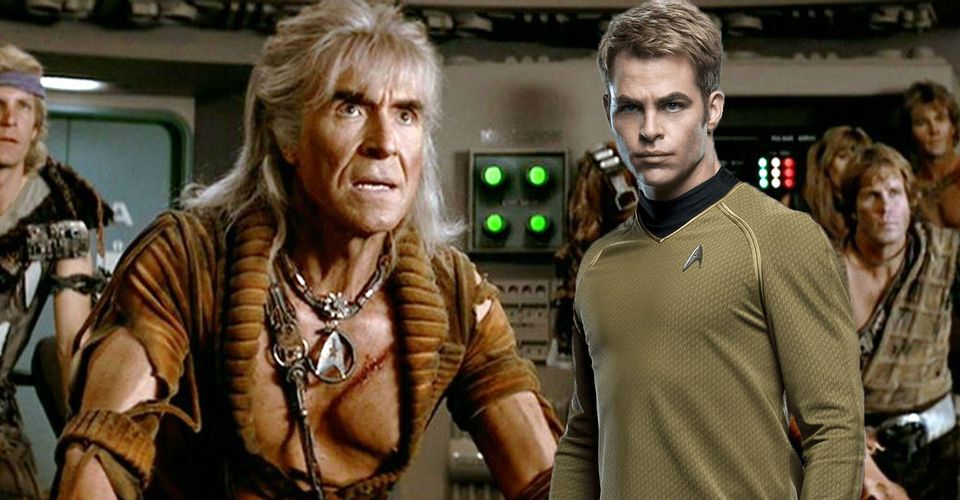

Do The Kelvin Timeline Reboot Movies Fit The Star Trek Movie Curse?

Whether the 2009 Star Trek movie is considered the 11th entry in the franchise, or the start of a whole new series, it’s an odd-numbered film and, therefore, should be rubbish. In truth, the J. J. Abrams reboot was a critical and commercial smash, reinventing the Star Trek story for a modern audience and beginning the cinematic careers of a brand new Enterprise cast. Trek purists may have found the director’s approach distasteful and the film’s use of lens flare might’ve spiraled hopelessly out of control, but it’s hard to argue that this isn’t the best odd-numbered Star Trek film to date.

Following the pattern, Star Trek Into Darkness should’ve been even better, and the sequel did receive a positive reaction upon release. Retroactively, however, Abrams’ second Star Trek effort has been heavily criticized as a derivative retelling of The Wrath of Khan with several awkward moments and a convoluted plot. Star Trek Into Darkness is perhaps the most divisive entry into the franchise’s cinematic canon, however, the odd-numbered Star Trek Beyond streamlined its approach. Focusing more on fun action scenes and swashbuckling adventure, the 13th Star Trek movie made less money than its predecessor, but garnered more positive reviews.

Evidently, the Kelvin timeline movies mess up the Star Trek movie law completely, and the partisan reaction to Star Trek Into Darkness makes it even harder to determine which movies are generally considered good or bad. It could perhaps be argued that the reboot films follow an inverse version of the odd-numbered rule, where the first and third films are good, and the second is panned. With Star Trek 4 officially cancelled, however, it’s unlikely fans will be able to put this reworked theory to the test any time soon.

Why Were The Odd-Numbered Star Trek Movies Generally Worse?

Humans have a natural urge to find order in chaos and make patterns out of the random, and the fact that odd-numbered Star Trek movies are generally considered inferior could certainly be an example of this phenomenon. However, there are perhaps some more empirical reasons for the existence of this curse.

Firstly, Star Trek: The Motion Picture‘s troubles can be directly traced to behind-the-scenes problems. Creative wrangling between Gene Roddenberry and Paramount, an ever-expanding budget and the studio’s desire to make a second TV series instead of a film all contributed to a doomed production. In contrast, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan learned from the mistakes of its predecessor and proved universally popular, arguably setting an unreasonably high bar of expectation for the follow-up.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier‘s lack of popularity can also be mostly accounted for. Leonard Nimoy’s success as director allowed William Shatner to push for the same position, despite being an amateur behind the camera. The production also ran out of money midway through filming, resulting in a dicey third act. Once again, lessons were learned, and Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country brought back Wrath of Khan director, Nicholas Meyer, who steered the franchise to success once again.

Moving into the era of Star Trek: The Next Generation, filming began on Generations only a week after the conclusion of the TV series, whereas a two-year break allowed Star Trek: First Contact to develop a far more fan-pleasing story featuring the Borg and time travel.

While it’s easy to paint the odd-numbered Star Trek movie rule as a fun coincidence or mythical Hollywood curse, it’s perhaps more accurately described as an ongoing cycle of avoidable production issues followed by a period of learning from past mistakes, before once again succumbing to complacency.

About The Author