Weird, Weird West: 10 Essential Cult Westerns

Westerns make up one of the widest and oldest genres in cinematic history and their famous iconography can sometimes paint a rigid, predictable, picture in people’s minds. But, truthfully, the genre has produced some of the strangest and most significantly revolutionary films to ever grace the screen. Though, not all of them were appreciated as such when they were released, finding devout audiences over time and despite mistreatment from critics.

Here’s our list of ten essential cult Westerns, big and small, to watch if you want to get a better understanding of film history. (Or if you just really like good movies.)

10 Chato’s Land

1972’s Chato’s Land was the beginning of a long and fruitful collaboration between tough guy screen icon Charles Bronson and eccentric director Michael Winner. Bronson’s eponymous Chato is an Apache who’s hassled to the point of murder. But it’s the posse of cutthroats and reluctant accomplices, assembled by Jack Palance’s glory-obsessed ex-Confederate soldier, who commit a far more heinous crime in the name of justice.

From then, the movie shifts from a moralistic Western to a proto-slasher movie as Chato picks them off one by one. Many have also drawn strong parallels between the story and Vietnam revisionist horror movies that wouldn’t appear in numbers for another decade.

9 The Great Silence

Sergio Corbucci’s remarkably bleak Spaghetti Western is remembered in popular culture either for its nihilistic ending or for the influence that it’s had on the genre as a whole. You’ll certainly see a lot of it in Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight and you’ll hear even more it in the scores from their shared composer, the infamous Ennio Morricone.

As was the convention with Italian movies of that era, the audio is entirely dubbed so it’s your choice as to whether you see the Italian dub or the English. The lead performances from Jean-Louis Trintignant as the titular gunslinger–who, as you may have inferred, doesn’t speak anyway–and Klaus Kinski’s unforgettable villain are intensified by the style though, and it brings the two unique actors together in a very unique way.

8 El Topo

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s hugely influential Western from 1970 is often credited as the first-ever ‘Midnight Movie’ and it became a byword for controversial weirdness in a legacy that endures to this day. A large section of it revolves around deliberately inflammatory remarks which Jodorowsky made while promoting the movie and they have become almost mythologized over time. There’s even one about Jodorowsky personally murdering several hundred small bunny rabbits with a fork just for one scene.

Like most of Jodorowsky’s work, El Topo is a heady mixture of religious iconography, and blatantly provocative shock value, that is largely open to interpretation. Film critic Pauline Kael’s review led to the birth of the term ‘Acid Western’ and you can feel El Topo in the subsequent films that would make that term a bonafide subgenre.

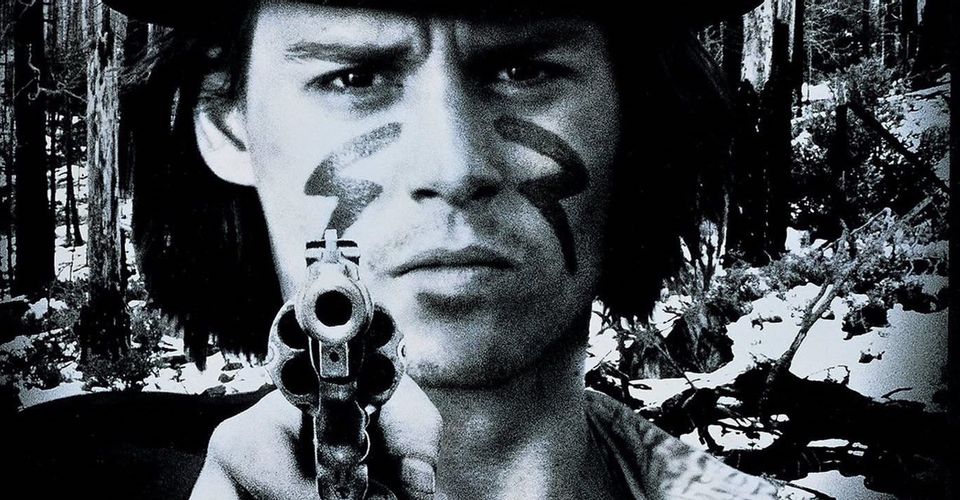

7 Dead Man

Jim Jarmusch’s 1995 Western Dead Man is seen by some as the culmination of the ‘Acid Western’ tradition started by El Topo. Like many of Jarmusch’s films, it sports an impressive cast of actors in bit parts that litter a sporadic story. But it’s mostly forged out of the odd couple pairing of Gary Ford’s lonely Native American–named “Nobody”–and Johnny Depp’s skittish city boy thrust into the life of an outlaw.

Shot entirely in monochrome and hauntingly scored in electric guitar by American folk-rock legend Neil Young, Dead Man is undeniably an incomparable trip. One that’s quite clearly inspired a number of great cult Westerns from the following decades.

6 Ravenous

Antonia Bird wasn’t the original choice to helm this odd Western horror movie. But, several weeks into filming, she found herself in the director’s chair after friction with producers resulted in the original director’s abrupt replacement with studio stalwart Raja Gosnell, who the cast apparently rejected in favor of her.

Bird would claim that this familiar experience of Hollywood backstabbing would inform her understanding of Ted Griffin’s screenplay about cannibalism in the Sierra Nevada and, despite Bird feeling locked out by producers in the end herself, Ravenous came out as weird as a big studio movie ever can. A quality exemplified by the remarkably strange score from composer Michael Nyman and Blur/Gorillaz frontman Damon Albarn.

5 Walker

Alex Cox’s 1987 sorta-biopic about William Walker’s disastrous filibustering–and short-lived takeover–of Nicaragua starts out as a semi-respectable, if left-field, Hollywood prestige period piece, sporting both a score from The Clash frontman Joe Strummer and a screenplay from Pat Garret and Billy the Kid writer Rudy Wurlitzer. But it gradually morphs into a satire of 20th century American foreign policy that abandons all pretense of metaphor and historical accuracy.

It was attacked from every angle at the time and its commercial failure was linked to Cox’s subsequent exile from Hollywood, although the reaction to Walker’s incredibly rare lampooning of American history’s depiction on-screen looks a lot more like blacklisting from a modern perspective. Its unrepentant weirdness and unabashed politics have, however, caused it to endure and find greater appreciation over the years.

4 Blazing Saddles

Mel Brooks’ beloved comedy is debatably his greatest work and a perfect example of a more crowd-pleasing–but no less biting–version of a satire on American history’s depiction in media. The addition of traditional screwball comedy to Brooks’ takedown of institutional racism made it much more palatable and marketable to a wide audience compared to a movie like Walker.

Considering how iconic Cleavon Little and Gene Wilder have become in their lead roles as Sheriff Bart and the Waco Kid, it’s strange to think that neither actor was Brooks’ first choice. With original Waco Kid, Gig Young, collapsing on the first day of shooting and studio executives refusing to insure the movie’s co-writer, Richard Pryor, for the role of Bart. Its very existence still feels a little miraculous to this day.

3 The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada

The directorial debut of actor Tommy Lee Jones is a strange, dark, comedic, and harrowing journey from Alejandro González Iñárritu’s ‘Trilogy of Death’ screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga. It follows Tommy Lee Jones’ Texas ranch hand as he seeks to avenge the unjust murder of his friend, the titular Melquiades Estrada, at the hands of Barry Pepper’s border patrol agent.

Released today, Three Burials would almost certainly be hounded morning, noon, and night by a wave of professionally outraged internet and media pundits who would call it ‘overly political’ and ‘prejudiced against real Americans’. Jones would pull similarly few punches with his comparably downbeat take on women and the West in his second feature, the also-brilliant The Homesman.

2 Ride the High Country

Sam Peckinpah was a roguish force in American cinema and his own works in the Western genre are considered as fundamental facilitators of many of the films on this list. So subversive and explosive was his image that it ended up being Ride the High Country, by far his most normal-looking Western, that ended up sticking out to movie buffs as his cult classic.

An unassuming film on many counts, Ride the High Country deceptively contains no less of Peckinpah’s fascination with lust, greed and violence. They just appear more quietly and subtly alongside themes that would become hallmarks of Peckinpah’s more well-known films, such as moral compromise, the death of the West and the concept of masculine honor.

1 Johnny Guitar

Nicholas Ray’s female-led Western may be the most widely, and openly, beloved film among filmmakers themselves throughout the latter half of the 20th century and beyond. It found instant acclaim among the budding French New Wave directors, but it was initially panned by critics on its release in America. Martin Scorsese would later assess Johnny Guitar as “an example of a minor film, grown to achieve the status of a classic” adding that, in the US, “people didn’t know what to make of it, so they either ignored it or laughed at it.”

It was Ray’s first film in color and his vivid use of it–which will be familiar to fans of his most famous film from the following year, Rebel Without a Cause–made it the indelibly striking experience that it is today. It’s an experience that could comfortably be called timeless.

About The Author